Is there a place on campus where I can learn how to address/talk to professors? I have been in the US for about six years now, but I am originally from a culture where one is supposed to show respect to people older than you. I therefore still cannot bring myself to address a professor by name (as my other fellow graduate students do), or write an email to them without putting in multiple “Thank you for your time!” and “Sorry to bother you…”.

When I read my own emails that I send out to professors, it’s cringeworthy, since I’m so deferential. It’s worse when the professors I address are just a couple of years older than me. I want to learn to get over this. My friend recently pointed out that calling someone “Prof. X”, and writing so many Thank Yous and Sorrys in email skews the power dynamic a bit too much, and that I should treat professors as colleagues if I want them to treat me as one.

How do I learn this? I hang out with a lot of American friends but somehow this is something I’m unable to learn. —Anonymous

This question was originally published in November 2016. The responses have been slightly updated for accuracy as of January 2019.

Hi, there. In order to address your question, I reached out to several campus partners. I hope their multiple perspectives and experiences are helpful.

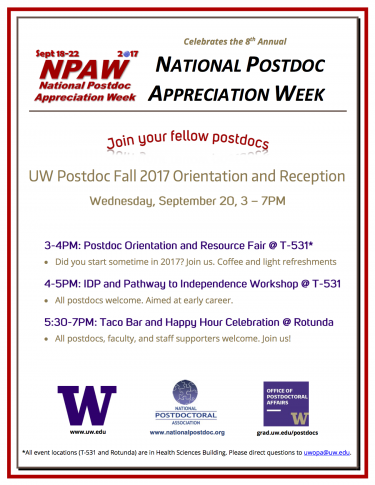

Ziyan Bai is a graduate student assistant with the Graduate School’s Core Programs and Office of Postdoctoral Affairs:

“For the past couple years, I have organized a workshop on “Communicating with Faculty” for international grad students. At the workshop, a panel of three faculty members and four advanced international graduate students from social science, science, engineering, and humanities shared communication tips and strategies including communicating in person or via email. We have a summary of notes from the panel.

I also get this question many times during my one-on-one mentoring with new international grad students. This is not an uncommon situation. The bottom line: find a middle ground that you find comfortable with the degree of reverence you show in the email or talking in-person. Usually international students find it uncomfortable if they try to “get rid of” their home culture in order to fit in. There is no universal standard in communication, so staying connected with home culture and being open to learn new culture at the same time is recommended.”

Note: The “Communicating with Faculty” Workshop is being offered this May. Details will be announced in the Graduate School Digest and on the Graduate School’s events calendar.

Era Schrepfer is the executive director of the Foundation for International Understanding Through Students (FIUTS), which offers a wealth of support and programs for international students at UW:

“We hear this question pretty frequently. I usually suggest visiting the professor during office hours and being totally honest about this with them directly. Just say, ‘I’m from XXX and in my country we are taught from an early age to treat teachers much more formally, so the culture in the classroom here is hard for me to get used to. I want to be successful in your class and for you to feel comfortable. What do you suggest to help me with this?’ Usually, they really don’t mind being treated more formally by international students, but it helps to start off the quarter with a conversation.

Sometimes, it’s easier to feel comfortable with a professor when you know them a little bit on a personal level, and it’s meaningful to the professor as well. So ask them questions about themselves. Have they ever been to your country? How long have they been teaching? Where did they go to school? It’s helpful to find some common ground with them and see them as people just like you. Power distance is one of the most challenging cultural elements! I know a lot of alumni who still struggle with it many years after coming to the US!”

Elloise Kim is the president of the Graduate and Professional Student Senate, and an international student herself:

“As someone who is from a similar culture, I totally understand why you are hesitant to freely communicate with people like faculty members. In my home culture, a respectful manner for people who are older or hold a higher position is obligatory. Yet, if people here can interpret your attitude not necessarily as carefulness but as cultural clumsiness, you may want to question for whom you insist to keep such manners.

I’d like to suggest to learn American cultural manners in the way you have learned English. In other words, think of it as a foreign language. Its syntax and phonetics would be very different from those of your original language. But, you have to learn and practice it in the way the language is spoken by native speakers. You do not become a totally different person while speaking English – rather, you are speaking another language still being yourself. Likewise, ways of communication need to be learned and adjusted. You can be very polite in a different way!”