With federal budgets getting tighter and the future uncertain, having a strategy for diversifying your funding portfolio is key to success. Gone are the days where an academic researcher might have a career fully funded by a single organization. Not only is it good for your bottom line, but diversifying your funding sources can also be good for creativity: some foundations or non-governmental organizations have different parameters and flexibility about what kinds of projects they fund.

In December 2017, we heard from two highly successful UW faculty, Drs. Chet Moritz from the Departments of Rehabilitation Medicine, Physiology & Biophysics and Dan Ratner from Bioengineering, who shared their strategies for success with diverse funding sources. We share a few of their tips and insights here so you can try a few yourself:

- Federal funding is diverse. Many UW faculty and postdocs have experience with NIH and NSF. But experience shows it can pay off to look beyond these traditional sources that are more competitive. For example, the Departments of Defense and Energy fund a significant amount of innovative research. Get creative about how your science can fit within other priorities and desired applications. Add a collaborator with relevant expertise, pivot to a new application, and find an informant with experience who can help you navigate the new language and formats of the applications.

- Take your work to the next level. The NIH and NSF invest in basic science and innovative discovery. If you are interested in bringing your innovations to implementation, dissemination, translation, or commercialization, you often need to look elsewhere for funding support. Fortunately, many foundations are highly motivated to bring discoveries to impact, and other entities such as the State are interested in implementation and commercialization. Search the state budget for line items dedicated to specific problems lawmakers are motivated to solve. Search the Foundation Directory to find a match for your research area and a foundation who values and invests in those areas.

- Don’t shy away from smaller grants. Do you need funds to kick-off new ideas? Small grants can help you get preliminary data or demonstrate a proof of concept. Smaller grants can help you build a relationship with a funder (governmental or private sector). At UW, postdocs have access to the Amazon Catalyst awards. Junior investigators can have an edge. Institutions and funding organizations want to invest in young, exciting researchers.

- Build a relationship and grow your connections. Once you get your foot in the door, build a relationship with the funder. Success breeds success, no matter how small. Celebrate and make visible what you’ve accomplished and who made it possible, whether the funder, the institution, the state, Congress, etc. Know your audience (your funder) and dedicate some time to a feedback loop that will grow and sustain your relationship.

Finally, grant writing inevitably involves disappointment. It can take seven submissions to get to one successfully funded project. Pay attention to reviewer feedback, do your best to match your idea and proposal to the funder’s priorities and formats, and develop resilience and persistence. It will pay off! We know you can do it, and we are right there working at this alongside you. Funding your research is a lifelong endeavor and the landscape is always changing; your ability to be responsive and pivot when needed is key.

Additional references:

- Federal Business Opportunities, to search for open calls for contractors to solve specific problems with governmental agencies.

- Broad Agency Announcements (BAAs) are included in grants.gov and provide more diverse federal funding opportunities.

- Foundation Center Directory, to search for in-depth beta on specific foundation funding. Note that to get access to more detailed information, you have to access via a dedicated Foundation Center site either at UW Tacoma Libraries or the Seattle Public Library (Central).

- Diversifying Portfolios: With funding tight at NIH, what are the alternatives?

- Diversifying Your Portfolio: Non-NIH Sources of Funding

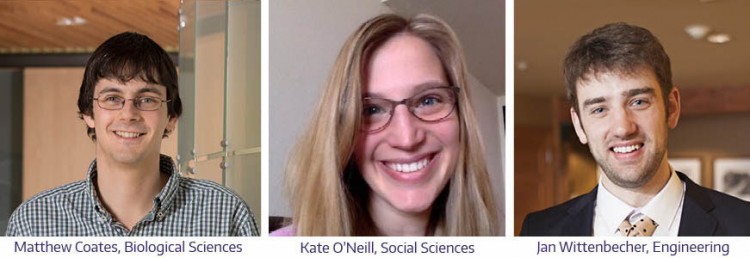

The Graduate School recognizes exceptional scholarship and research at the master’s and doctoral levels. These awards recognize a thesis and a dissertation in four categories: Biological Sciences, Humanities & Fine Arts, Mathematics, Physical Sciences & Engineering, and the Social Sciences. Meet the winners of this year’s

The Graduate School recognizes exceptional scholarship and research at the master’s and doctoral levels. These awards recognize a thesis and a dissertation in four categories: Biological Sciences, Humanities & Fine Arts, Mathematics, Physical Sciences & Engineering, and the Social Sciences. Meet the winners of this year’s