Rooted in community

Ph.D. candidate Olivia Orosco is reimagining care and resilience in environmental justice

Growing up in a small agricultural town in northern California, Olivia Orosco often heard her father’s reminder as they drove through the expansive farmland, “This is why you go to school, Mija. So, you don’t have to work outside like your grandfather or I.” In an agricultural community, field labor jobs were common ways people in her community would earn money. For Orosco, now a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Geography, the outdoors held both beauty and a complicated history.

"In my head I had, this rhetoric of the outdoors being violent or exploitive of Chicana.

At the same time, I have always loved plants and being outside and exploring the beauty of nature.”

That tension, between curiosity and caution, shaped Orosco’s early interest in environmental justice. Her undergraduate studies opened up deeper questions about why some communities have very different relationships to land and nature. Through activism work in her undergrad, Orosco knew she wanted to continue her community work and began working at immigrant serving community organizations, first in Salem, OR and then in Tacoma, WA.

A path to graduate school

When Orosco arrived at the University of Washington for her master’s degree, her academic trajectory began to shift. Orosco became increasingly interested in care work—not just as a social act, but as an intellectual framework. Through her studies, she connected this idea of care to her relationships with plants, community and family. Whether tending to a garden or nurturing a houseplant, Orosco saw caretaking as an extension of love and responsibility, deeply tied to her identity as a sister, a new mother, and community member.

“Everything ends up better when we build strong communities,” she says. “Kids are raised better, plants are stronger, and our neighborhoods are more alive when we know each other.”

These experiences helped Orosco see how environmental issues intersect with systems of oppression—from colonization to immigration policy. Yet, as she continued her research, she began to question the focus on harm that dominates environmental justice work. Constantly centering pain and violence, she realized, can obscure the joy, care and creativity that also define communities of color.

Her dissertation now seeks to shift from “damage-centered” to “desire-centered” narratives—a concept inspired by scholar Eve Tuck. Rather than solely documenting environmental harm, Orosco’s research celebrates the ways people nurture memory, hope and belonging through their relationships with plants. She studies how communities plant seeds that honor ancestral traditions, reclaim cultural memory and imagine futures of care and abundance.

Planting, she says, is an act of faith: “I’ve been building with my own experiences around desire and harm in outdoor spaces towards more uplifting work. I think we need that now more than ever.”

Orosco’s work challenges the notion that Black and brown communities exist only in struggle, instead illuminating the wholeness, joy and resilience that bloom alongside resistance.

Research with care, connection

That experience during her master’s shaped her approach to research as an act of listening. Rather than entering conversations with a predetermined agenda, she learned to let her participants guide the process, listening deeply to what they shared, and even more importantly, to what they didn’t. Orosco describes her interviews as long, tender conversations filled with grief, love and memory. She learned to “hold” that space for people—to witness their pain while connecting their stories to a larger social fabric.

This patience and openness transformed her approach to research. She began her Ph.D. fieldwork asking participants about the distinction between “gardeners” and “farmers,” curious about how people saw themselves in relation to food and land. But the question never resonated. Instead of forcing it, she let the research evolve. She began to see how language and identity around growing food were shaped by generation, politics, and community rather than by simple definitions. The process taught her that good research requires humility—the willingness to follow where stories lead, not where you expect them to go.

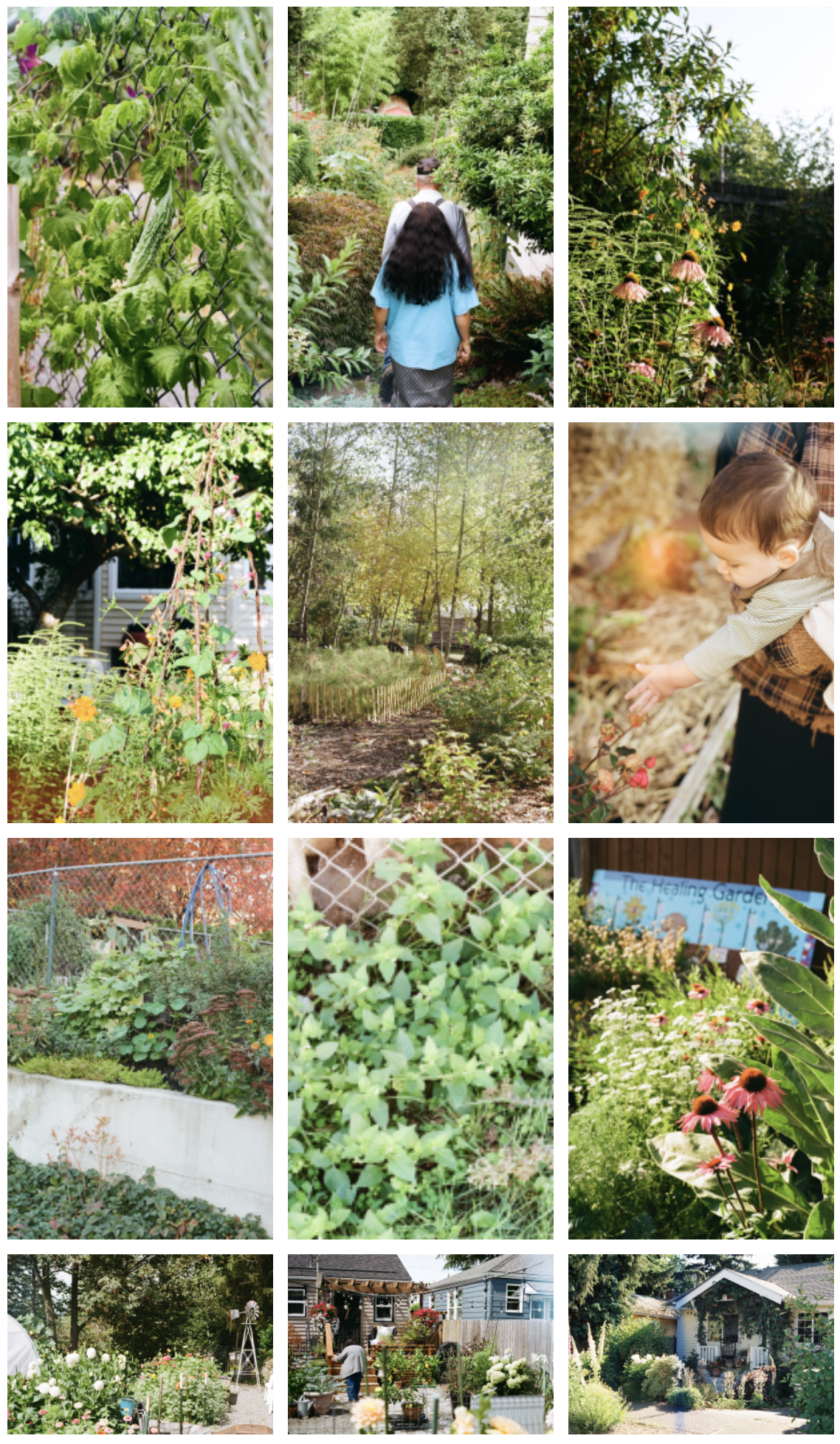

Over time, Orosco found ways to weave her creativity into her research. A visual thinker, Orosco folds photography into her work, using her grandparents’ old analog camera, she captures the intimacy of people with their plants, finding that photography helps her stay grounded in the present moment.

“The act of photographing someone in their garden is a way of honoring them, of seeing them fully,” says Orosco. She plans to bring her participants together for a community gallery show that celebrates their shared connections to land and to one another.

Staying in graduate school

Orosco’s journey at UW was made possible by key graduate fellowships. When Orosco began her master’s in the fall of 2019, she couldn’t have imagined how quickly the world—and her plans—would change. As COVID-19 canceled visits and disrupted graduate admissions across the country, she faced a difficult decision: accept a competitive offer from another university or remain in the Seattle area and attend UW. The decision to stay was made possible by the GSEE (formerly GO-MAP) Recruitment Fellowship, which lifted a significant financial burden and allowed her to focus on research during her first year without the pressure of teaching.

“That fellowship was foundational,” she says. “It set the tone for my graduate experience and made UW a viable and supportive home for my studies,” says Orosco.

That early support led to the Ford Predoctoral Fellowship, a highly competitive three-year award that allowed her to pursue research without the pressure of additional work commitments.

Now, as she enters her final year, the Graduate School’s Final Year Dissertation Fellowship will give her the time she needs to complete her dissertation, apply for jobs and postdocs, and prepare for the next stage of her career.

“Trying to live in Seattle on a modest stipend, balancing academic work with family and community commitments, and still finding the mental space for creativity and research,” she says.

The GSEE fellowship didn’t just bring her to UW; it helped her stay, grow and thrive, so she could make lasting change in her community.

“This fellowship gave me something invaluable: time,” says Orosco.

By: Tatiana Rodriguez, UW Graduate School

Published on November 10, 2025